By Yvette Greslé.

Photo credit: Sofie Knijff

Despite the sincerity of the artists who have brazenly maintained a relationship in their work with the black body, there is a certain over-determination that accompanies their gestures. They seem to neglect the fact that the black form is as much a grotesque bearer of traumatised experiences as it is the abject vessel of race as a point of differentiation. More than alerting us to how the stereotype fixes its objects of desire in that freeze-frame of realism, as prior knowledge, the work of these artists exacerbates the stereotype by replaying it, perhaps unconsciously, as if it had always been factual.

(Okwui Enwezor). [1]

I have always suspected that most South Africans do not understand what racism is. There is a disconnect between what happened in the past and our experience of today. I feel that we wiped the memory of racism’s definition as according to our experience.

(Simphiwe Dana). [2]

Brett Bailey’s performance-installation Exhibit B casts black performers in roles that require them to perform his theatrical fantasy. Interviewed for the Agenda Magazine blog, in 2012, on the occasion of a prior staging of Exhibit B in Brussels, Bailey says: ‘I’m bringing five performers with me. The others are Africans living in Brussels. Some of them are asylum-seekers. And yes, I do put them in glass displays and cabinets and things like that. One by one, the spectators go in and do a tour’. This grotesque exploitation of asylum-seekers, and its associated reiteration of historical racial abuse, is facilitated by Bailey’s company ‘Third World Bunfight‘. In a BBC video, which includes rehearsal footage, the mannered, and controlled nature of Bailey’s approach to performance is evident. He tells us: ‘I am a performance-maker. I come from South Africa. I am interested in beauty and the objectification of people. Turning them into beautiful objects. I am very interested in the seductive quality of beauty. Then also in what lies behind that beauty and the horror that is there’. Exhibit B, is in Bailey’s words:

Somewhere between performance, theater and an art exhibition. I read a book called Africans on Stage which gave me insight into the phenomenon of human zoos and that was the catalyst for making this work. What was behind human zoos was the representation of the Other in a particular way, to de-humanise and objectify them. I take colonial history. I take the atrocities that were committed under colonialism right from the 19th century all the way up until the liberation of the 1950s and 1960s. And then I look at the residues of racism. Or the racism that we are still living with today (BBC video).

Bailey does not pause to reflect on the meaning of this ‘we’ and his own complicity in histories of racism, which he re-inscribes in Exhibit B. An audition call-out to black performers for the forthcoming Barbican iteration of Exhibit B can be found here. This document is revealing both in what it says about Bailey’s complicity in racial type-casting, and the historical rendering of the bodies of black women: ‘Please note that two women will be required to perform topless’ and ‘A range of African and Caribbean men and women of various heights will be cast (including specifically 1 man and 1 woman who are no taller than 5.2 ft)’. [3] As Achille Mbembe puts it:

We should remind ourselves that, as a general rule, the experience of the Other, or the problem of the “I” of others and of human beings we perceive as foreign to us, has almost always posed virtually insurmountable difficulties to the Western philosophical and political tradition. Whether dealing with Africa or with other non-European worlds, this tradition long denied the existence of any “self” but its own. [4]

Visual strategies that offer a radical critique of historical practices, of the problem of the ‘I’ and of the ‘Other’ (and the relevance of this to the history of white supremacy in South Africa) appear to be absent from Bailey’s vocabulary. On a petition, organised by journalist and activist Sara Myers, on Change.Org, Myers writes to black publics: ‘I’ve been sent a link to a preview of the Exhibit I want you to watch it not as spectator or as an observer. I want you to watch it through the eyes of your DNA. I want you to experience the atrocities our ancestors experienced through the hands of white supremacy. Though it’s a part of our history it’s by no means the whole of our story.’ This statement tells of the relationship between historical racial abuse, the relationship to trauma, and the imposition of voices that speak from a position of whiteness and the power relations that this implies. It is this voice and this history that Bailey discounts. The writer and scholar John Edwin Mason tweeted @johnedwinmason, on the 12 August: ‘Well, at the very least, he seems incapable of asking the deepest questions – those that involve himself’. Mason notes in discussions, on Twitter, Bailey’s ‘willingness to ask his actors to reenact their ancestor’s humiliation’.

Circulating on Twitter are references to colonial exhibitions in the work of Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez-Peña. An article published in BOMB magazine contextualises this: ‘In March 1992, performance artist and MacArthur Fellow, Guillermo Gómez-Peña and writer/artist Coco Fusco locked themselves in a cage. Presenting themselves as aboriginal inhabitants of an island off the gulf of Mexico that was overlooked by Columbus, their spectacle provided a thorn in the side of postcolonial angst’. [5] But here the artists, who themselves embody histories and lived experiences of race, deploy strategies that exist in a considered, self-reflexive relation to the discourse on race. Both artists are aware of the critical capacities of performance: they deployed strategies such as parody and the actual bodily and tactile blurring of the space between audience and performer. Most importantly, they placed themselves in the cage. Artist and Editor Nathalie Dubruel (@mudlarky) circulated, on Twitter, the video clip (‘The Couple in a Cage’) showing aspects of this performance (which appears on YouTube).

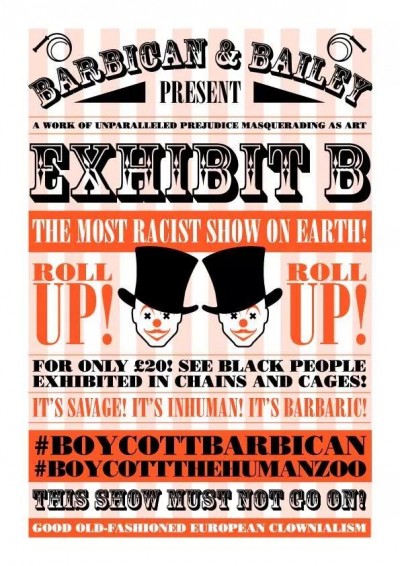

Exhibit B has sparked controversy across the cities in which it has recently appeared: Berlin, and Edinburgh, and is due to arrive in London at The Barbican in September. The Barbican will also be staging Bailey’s Macbeth. Accounts of Exhibit B and critical responses in the United Kingdom have appeared in The Guardian, WOW 24/7, The Telegraph, The Financial Times, The Voice, and Ligali. Critiques have also appeared on independent platforms such as Minor Literature[s] and blogposts, notably that of artist and performer Selina Thompson. Sadiah Quereshi, a lecturer in Modern History at the University of Birmingham has written an historical account of European practices of human exhibits from the 15th Century to the 19th Century. She includes archival research that lends ambiguity to European/African relations: ’In 1899, news broke that Kitty Jewell had become engaged to the star of the Savage South Africa exhibition at Earl’s court, Prince Peter Kushana Lobengula’. [6] Quereshi’s response to Exhibit B is published in The Conversation.

Bailey claims that his work has a political and an ethical purpose: he speaks of his relationship to apartheid South Africa. But responses posted on social media, including Twitter, over the past two weeks, speak to what is so unethical about Bailey’s work: ‘If your intent is to subvert the long history of human zoos, why are you still using Black bodies? Why not address the white gaze? (Mikki Kendall @Karnythia). In response to the criticism, and indeed anger, mounting in London, the Barbican issued a statement (which they tweeted to me personally on 22 August 2014). This counter-argument, or rather Public Relations script, was written (we are told) by Toni Racklin (Head of Theatre); Jan Ryan (Director UK Arts International and Brett Bailey (Director of Exhibit B) and is an example of assumption-making and condescension. It is inappropriate as a form of delivery to audiences who are visually literate; it is inappropriate to audiences who have lived and embodied experiences of racial abuse and discrimination. It is a document that enlists quotes from actual performers, in positive vein, although I personally, interested in what is unsaid, am sceptical. John O’ Mahony’s piece for The Guardian suggests that the relationship between work and performer is not that straightforward: ‘The only problem is that the young black performers, cast locally at every stop along the tour, aren’t quite getting it. “How do you know we are not entertaining people the same way the human zoos did?” asks one. “How can you be sure that it’s not just white people curious about seeing black people?” adds another.’ [7] Barbican responses to criticism speaks to the convergence of Public Relations, Power, Race and cultural institutions in the United Kingdom. Bailey appears unaware of one of the most critical questions of post-apartheid South Africa: Who speaks, for whom and how? His own complicity in this history is absent from his work. In response to the outrage and criticism, in London he replies:

Exhibit B is not a piece about black histories made for white audiences. It is a piece about humanity; about a system of dehumanisation that affects everybody in society, regardless of skin colour, ethnic or cultural background, that scours the humanity from the ‘looker’ and the ‘looked at’. A system that emphasises difference rather than similarity. A system that gave birth to the hegemonic regime of separation in which I grew up, and which continues to haunt the people of my country. The kind of systems we need to guard against (Barbican statement).

As I write this in August 2014 I wonder how those affected by, for example, the events of Marikana in South Africa would feel about this version of humanity and about Bailey’s assumption of a ‘we’. In August a controversy around white South African students enacting Blackface and caricatured dress-ups of the bodies of black South Africans erupted on Twitter and Facebook. The South African writer and intellectual T.O Molefe responded with a Storify critique. It is as though Bailey imagines himself an auteur offering audiences (upon whom he projects his many assumptions) a lesson in racist abuses. But his lesson is crudely wielded. Exhibit B – the title actually says it all – is a stage set of inanimate objects including the silent black performers. The beautiful and evocative music that accompanies the installation functions manipulatively: It lulled me into an emotional space within which I almost forgot what it was I was looking at. Bailey’s performers must not only embody traumatic histories choreographed by a white South African man but also offer up their private narratives and experiences of racism for the scrutiny of white audiences. Racklin tells us: The final room of the installation contains some of the [testimonies of the performers] reflecting on both their involvement in the piece and providing their personal experiences of racism and prejudice they’ve experienced in their own lives’ (Barbican statement). In a crude appropriation of ‘the gaze’ we are told by Racklin: ‘Visitors to the performance are forced to confront the reality of this dehumanizing treatment with the performers directly meeting the eye of audience members’. But who decides what it is this gaze means? If an analysis grounded in racial abuse and trauma were to be applied to Bailey’s tableaus what would emerge would be very unsettling indeed. Furthermore, The Barbican is charging £20 to view the spectacle: the historical relationship between racial violations and profit is re-visited here, unambiguously.

There are contradictions present in Bailey’s response to criticism. In the audition call-out, cited earlier, he states: ‘Since 2001, as a white South African performance maker, I have travelled regularly to Europe with casts of black performers to present works at festivals for the diversion of (mainly) white audiences’. In the Barbican Statement, we read: ’Exhibit B is not a piece about black histories made for white audiences’. He tells us too: “Nowhere do I term Exhibit B a ‘human zoo’”. And yet the term ‘human zoo’ is mobilised by Bailey on a number of occasions in discussions of the work. The BBC video is one example.

That Bailey is a South African classified white by the apartheid regime is of importance to the debates about this exhibition. His documented responses to the criticism (directed at him) speaks to some of the social and political attitudes that apartheid South Africa produced. Twenty years after the official transition into democracy and one Truth and Reconciliation Commission later we find ourselves in a social and political space within which past overlays the ever troublesome concerns of the present. This is a context where race is still visibly inscribed, not only in the major disconnections that prevail in social and political relations but also in the visible reminders of apartheid era urban planning. Events such as Marikana speak to the ambiguities that exist between apartheid/post-apartheid social and economic structures: South Africa’s brutal, historical relationship to capitalism (and its relationship to race-related abuses) is all-pervasive. There is not one South African, classified white by the apartheid administration, who can claim to be untouched by the regime’s deliberate and calculated project of white supremacy; its ideologies and systems of indoctrination. So systemic and insidious was its campaign to categorise and separate racial groupings and hierarchies that not even the most liberal or left-leaning white South African can claim not to have absorbed some form of racial prejudice (or not to have benefited in one form or another from the structural privileges which it engendered). I am not calling for a performance of guilt and self-flagellation but rather some humility, and careful, considered dialogue.

One of the most ubiquitous examples of the overlay between apartheid South Africa and the present is the belief (held by the privileged) in the absolute authority of one’s own voice. This voice is not to be challenged or questioned. The critic runs the risk of being condescended, shouted down, stonewalled, diminished or simply ignored. If the critic is perceived to hold little social, political or economic power there is only a void in which to protest. It appears that this is not only the preserve of the conditions that apartheid produced. In a disconcerting overlap of geographical-political conditions the Barbican’s response to the criticism wielded at Bailey’s Exhibit B is reminiscent of South Africa past and present. It opens up a space for thinking about cultural institutions in London and their relationship to histories of slavery, colonialism, and contemporary forms of racism. It is as though the Barbican, similarly to cultural institutions in South Africa, find it difficult to imagine multiple audiences shaped by more than one subjectivity. The Barbican has responded to criticism with a document that finds itself unable to communicate in a considered and human manner with the critiques that are currently being wielded at Exhibit B. This is one of the most distinctive markers of privileged whiteness: The absence of humility, of a self-reflexive, considered dialogue with subjects who have a direct, historical (and traumatic) relation to racist lineages, overt and insidious. And this from an institution located in a city that so deliberately stages the language of multicultural and cosmopolitan.

Endnotes

[1] Enwezor, O. ‘Reframing the Black Subject: Ideology and Fantasy in Contemporary South African Representation’. In Oguibe, O and Enwezor, E. (eds) Reading the Contemporary: African Art from Theory to the Market Place. London: Institute of International Visual Arts, 1999, pp. 376-399. See: http://www.iniva.org/library/archive/people/e/enwezor_okwui/reframing_the_black_subject_ideology_and_fantasy (Last accessed 24 August 2014).

[2] Dana, S. ‘Don’t wish the rainbow on Palestine’, Mail & Guardian, 15 August 2014. http://mg.co.za/article/2014-08-14-dont-wish-the-rainbow-on-palestine (last accessed 24 August 2014).

[3] See the work of South African scholars such as Pumla Dineo Gqola and Desiree Lewis for a discourse on gender and race. Refer too to the critical art practices of South African women artists notably Tracey Rose.

[4] Mbembe, A. On the Postcolony. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2001, p.2.

[5] Johnson, A. ‘Artists in Conversation: Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gómez-Peña’. BOMB Magazine, Issue 4, Winter 1993, http://bombmagazine.org/article/1599/ (Last accessed 25 August 2014).

[6] Quereshi, S. ‘Exhibit B puts people on display for Edinburgh International Festival, The Conversation, 11 August 2014 http://theconversation.com/exhibit-b-puts-people-on-display-for-edinburgh-international-festival-30344 (Last accessed 25 August 2014).

[7] O’ Mahony, J. ‘Edinburgh’s most controversial show: Exhibit B, a human zoo’, The Guardian, Monday 11 August 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/stage/2014/aug/11/-sp-exhibit-b-human-zoo-edinburgh-festivals-most-controversial (Last accessed 25 August 2014).

Refer to an interview from a public discussion (transcribed by Nathanael Vlachos) that took place between Brett Bailey and Anton Krueger as part of a series called ‘Talking Arts’ at Thinkfest, at the 2012 National Arts Festival held in Grahamstown, South Africa.

See: Coombes, A. Reinventing Africa: Museums, Material Culture and Popular Imagination in Late Victorian and Edwardian England, United State: Yale University Press, 1997.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Yvette Greslé is an art historian, writer and blogger. She is currently completing her PhD, on South African video art, history and traumatic memory, at University College London. Yvette is a senior editor at Minor Literature[s]. Her art criticism has appeared in ‘this is tomorrow’, Apollo Magazine (blog), Photomonitor and Art South Africa amongst others. She is also a Research Associate at the University of Johannesburg. She tweets @yvettegresle.

First published in 3:AM Magazine: Wednesday, August 27th, 2014.