By: Gillian Schutte

Suicide is on the increase – especially among the youth.

Statistics from the South African Depression and Anxiety Group (SADAG) show that 9% of all youth deaths are due to suicide and that this figure is on the increase. In the 15-24 age group, suicide is the second leading – and fastest growing – cause of death. Children as young as 7 have committed suicide in South Africa. Every day 22 people take their lives.

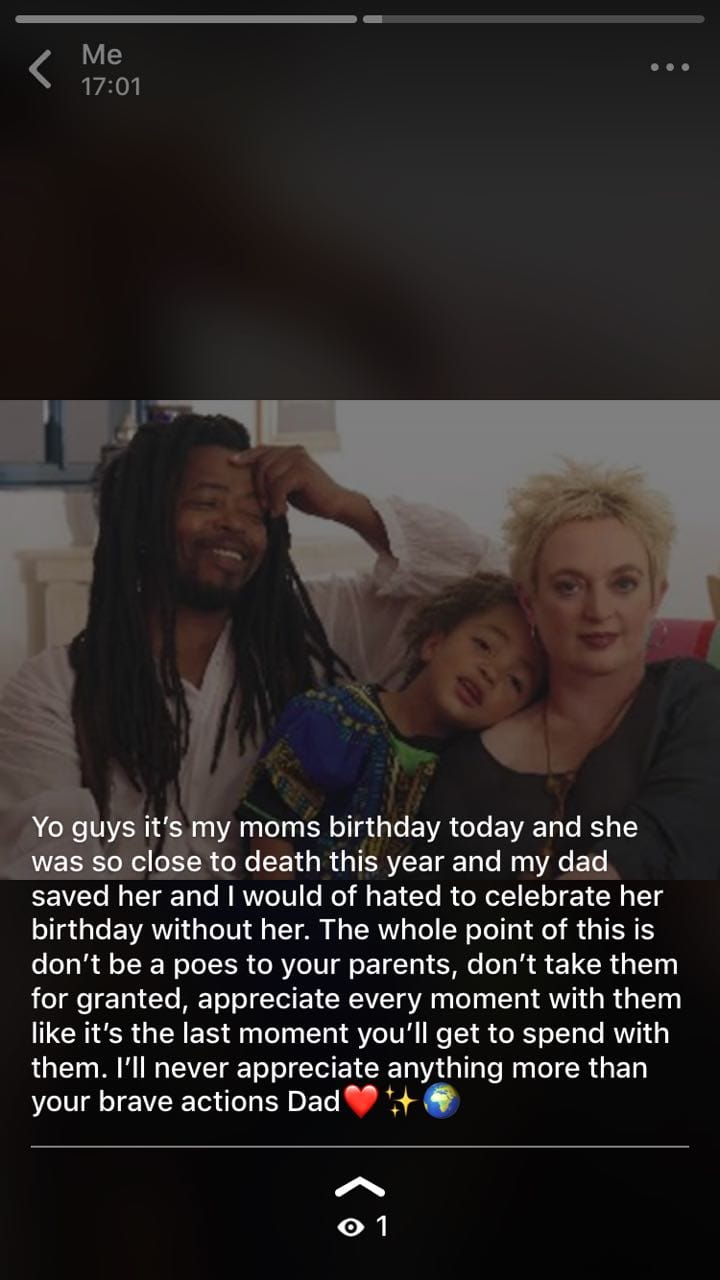

I had gone over these statistics when writing about depression and unemployment over the years. I never imagined that I would have to relate these statistics to my reality . But I did when on 1 December 2019, Sipho Singiswa and I, lost our only son, Kai Singiswa, to suicide.

Kai had just finished second year university exams and was ready to enjoy his holiday. He was doing well at Wits film school, was popular and full of fun. He had spent the week with a few friends in and out of our house, and the weekend at our home with one of his best friends. On Saturday they went to a car wash event. As usual he hugged and kissed us good bye and as usual we told him to stay cool, not drink too much and keep safe.

Like many parents we worried about our son out there. What if he got attacked for his cell phone. What if he got into a physical brawl and something irreversible occurred? What if there was a car accident? But when he turned 18 we had to let him be his own person. He had recently turned 20. We could only keep the lines of communication open, share knowledge with him, give him boundaries and trust in his sweet nature to protect him from harm.

The next time I saw Kai was the following morning. He arrived home upset and I could see he had been crying. He was upset about a series of events that culminated in an altercation with a friend. His friend had told him no one likes him anymore and that he was worthless. My son thrived on loving and being loved in return. He displayed the hallmarks of a highly sensitive individual and empath. He had spiralled into a dark hole of self-loathing and despair over the course of the night.

I held him and began to speak him through his anguish. I reminded him about his strong personal qualities and his talent in filmmaking. I spoke to him about the fickle nature of social groups and reminded him of what an honest and forthright person he has always been. I told him how much we cared for him. Sipho came outside and asked why we were in the hot sun. I told him our boy was upset and we went to the lounge to speak about it.

Kai and Sipho spoke father to son and Sipho counselled him with love and concern. After the session Kai high fived us, hugged us and said he was going to bed. He seemed stable and in better spirit. I offered him tea and he said he was going to drink water and sleep it off as he always did. He told us he loved us and went to his room.

Sipho and I discussed what more we could do to help Kai through this transition from boy to man. It seemed so hard for him. He had begun to suffer from anxiety and depression and, like many of his peers, was on anti-depressants. For the most part he was happy, highly functional and socially popular. He got out of bed every day. He finished his assignments at varsity and his marks were good. He spoke to us about his daily life and he partied with friends.

After our discussion I got dressed to go to the shops relieved that my child was sleeping it off. On the way out I went to check up on him. That is when I found Kai hanging from his gym.

There are no words to describe what happens to a mother who finds her child after suicide. Call it an atomic explosion that eviscerates everything you ever believed to be true. Your solar plexus implodes, your heart shatters and your womb is torn from your body. You hear a disembodied primal mother scream that is yours and not yours. You fall into a timeless black hole with no material safety holds to grab onto, and you keep falling.

Sipho had to take Kai down while I tried to phone an ambulance through my screams. He was the father who had cut the umbilical cord of his son when he was born and now he had to cut the cord from around his neck at his death. His pain and trauma is immeasurable.

My first instinct was to go off all social media on the morning we found Kai in his room. But he was a popular boy and many of his friends were in anguish when they heard the news. In no time youth media was adorned with photos of our child and speculation was rife. I wanted to be the guardian of his truth and so I made the decision to let people know what had happened. Except that what I shared on social media was only a fraction of the story of the complex inner life of a boy child born into a time in the world where there is a crisis of meaning, where depression and anxiety is almost the norm for the youth of today, where justice is nebulous and where competition and materialism are the skill sets taught to our children through multiple social media channels that overwhelm young minds.

Societal Pressure in a world of artifice

We can no longer ask the question why our children are choosing suicide over life.

We need to reflect instead on what this current era offers our children and why it is not working for them – because if we were to be totally honest we would acknowledge that they live in an era of cutthroat materialism that aggressively sells them the idea of instant gratification instead of patience and compassion. This can only be a shallow and empty path, which they are pressured to pursue by society at large in order to grab at success. Many are led to believe that they will be one of the lucky few who make it on YouTube on a par with Kim Kardashian. Yet underneath this aspirational trajectory the youth are craving to feel real, to feel loved, to feel connected in the world. Social media can only offer them a false sense of connectedness and one so tenuous it can all come crumbling down in an instant.

In this era of artifice, where fake news, fake tits, twits and duck lips crowd their social networks, our children unconsciously crave authenticity. They are faced with multiple stresses and demands and those who are wired to be empathetic and sensitive, experience cognitive dissonance and an ongoing existential crisis in this world that demands ego and more ego.

This is a catastrophe experienced by the youth globally and this intensity is magnified in a country such as ours, where they are forced to witness massive social cleavages, and if middle class, they are expected to normalise this reality. The sight of toddlers virtually shackled to street corners with parents begging from those in cars, impoverished youth washing windscreens for a buck, and sprawling shanty towns next to opulent neighbourhoods, are supposed to be ignored somehow. And what of the youth that live this reality as the desperately poor? Their lives become cheap, they turn to Nyaope, petty crime and other self-harming violence.

These times that we live in have been described as ‘traumatic experience’ for all people but mostly our youth, who are terrified of a world that births a Greta Thunberg and her apocalyptic forecast of environmental death and destruction in the near future. Many already face a daunting reality where unemployment is rife, fresh or potable water is fast becoming a scarcity, fake food is packaged as healthy and GMO is forced upon them via staple foodstuffs. They are faced with the unnerving future of global warming, crime, geopolitical terrorism and possible displacement through capital driven development and war. And amongst all this madness, this greed and inhumanity, they are told to become a success, to join the society of cutthroat competitiveness and pull themselves together.

Add to this onslaught sociohistorical decimation of family structures, peer non-acceptance and betrayals, their own trepidation about an uncertain future and a sense of terror about not ever being able to achieve their expected goals. Who would not be overwhelmed with a sense of hopelessness, and feelings of worthlessness? The conflict in them is a heightened one at their age-of-becoming and the inner crisis overwhelms them. So tenuous is their hold onto meaning in this environment of falisty that if there is any shift that upsets their already fragile balancing act – they are likely to be pushed to the very edge of despair for reasons we might consider fickle. We might even ask them to man up or grow up when what they need to hear is that they are loved… really valued and that there is hope.

Our son never could ignore these glaring contradictions presented to him in everyday life. He was hyper aware of the many historical and current injustices in our country and cognisant of the social violence heaped upon the majority. Like most middleclass youth he too tried to erase this truth from his conscience through partying and the pursuit of pleasure, and like many young ones this drove him to look for peer relationships where none existed and left him dissatisfied, hurt and sometimes angry.

As parents there is little we can do about their choices when at a certain age in their development our children place their hope in these peer relationships – by their deep connection on the spiritual or hedonistic level. This is where they find their sense of self in relation to others. Our artistic sensitive kids soon find their escapism in sad boy subcultures that romanticise suicide and birth a philosophy that speaks to concepts such as the 27 Club, where they joke about partying themselves to death before they reach adulthood, because there is no meaning left for them in a world that builds binary on top of binary and manufactures faux morality, faux politics, and an economic system that will never deliver anything that satisfies what it means to be fully human, to be truly free, to be kind, to be loving and compassionate. They party hard so that they can forget for a moment that we live in a global reality of cruel and mammoth extremes.

And this does not always work. In fact, it throws them into more crisis when they come to the realisation that they are bonded in emptiness and a lostness that will never fulfil their state of constant craving.

This white supremacist neoliberal capitalist system has robbed our youth of reflection, of security, of faith in their inner life. Their libidinal is no longer about their own minds, their own passions and their own joy felt in the connection between mind and body and soul. Joy is packaged in labels, chemical highs and material oblivion. And those not born white are left with the added anxiety in the knowledge that skin colour often determines whether they will be the recipients of material and personal security.

My son was a loving and compassionate soul. He was grounded in love. He cared deeply about those close to him. He cared about those who suffered around him such as homeless people and he always took the time to greet the less fortunate on his path and share a smoke or a laugh with them.

Like many of his peers he lived this existential crisis in real time and he spoke to us about it often. He internalised his fear and developed what he referred to as his dark passenger, a part of himself that he felt he had no control over. It was that injured aspect of himself that could never quite match the joyousness of his childhood with the reality of the world today. The idea of a future escaped him though he was provided with all the tools to access a stable future.

MEDIA ONSLAUGHT

Kai’s feelings of hopelessness and anxiety were also exacerbated by what he had witnessed unfurling in our lives as I became the target for mass cyber-attacks and death threats because of the nature of work I do. He was aware of the danger to our lives as a family when men parked outside our house for some weeks after the judge Mabel Jansen story broke and we received threatening messages in our postbox and on social media.

He also had to be made aware of the sensationalist tabloid reportage on an accident that happened on our film set in 2018 on which a close friend of ours, Odwa Shweni, fell to his death when a cast member took it on himself to call the first take in the absence of the director and AD and then allegedly set about proliferating a fake narrative of what happened in order to take the heat off his pivotal role in the accident. I had also reached the precipice of death in this accident and Sipho had pulled me from the edge in that split second before I fell to my death. Our beloved son Kai had to live this traumatic aftermath with us as we mourned the death of Odwa while many of my detractors pushed out multiple lies and used the death of our friend as a political football – the utmost manifestation of the norms and values of this fake news hyper ego driven world.

Kai cared for and protected us around this time and we tried to protect him from this cataclysmic unfolding of accusations and declarations of guilt on a matter that remains sub judice till today. We had hoped that this defamation campaign would not enter his world out there but it did when, in one of his Wits film school lectures, a Sunday Newspaper article was used as a reference about how not to make a film and our child was deeply upset and angry. We have to ask how, in an institution that prides itself on educational values and excellence, an article that clearly states the case is sub judice, is taught as fact.

And we have to recognise that this is exactly what happens in a neoliberal corporatized reality where truth no longer holds as much sway as sensation and the pornographising of tragedy for revenge and clicks. When Kai told us of this lecture, he pretended to be casual about it but in the weeks of our mourning when many of Kai’s distraught friends visited our home, I was told by one of his close friends that he had relayed the story of the lecture and the event to her brother and he was angry, distressed and tearful. My heart broke when I realised exactly how this cataclysmic event had impacted our son and how he had, in true Kai nature, tried to protect us from his own trauma around this event.

Our young man was a special soul, a caring soul and he loved to have fun. He cared too deeply as an empath. If his love was not reciprocated, his entire reality was threatened and he would rage against those who created this imbalance. He craved for balance and a world that reflected back his empathy and his capacity to love. He wanted kindness. He wanted his parents to be safe and he loved us a fiercely as we loved him. His line of communication was open and we spent many a time discussing his crisis. We did all we could to help him navigate this difficult transition from boy to man – but in the end, the hurt and the trepidation and the anguish that he had bore witness to overcame him and he found this world too painful and limited a place to continue to inhabit.

Our son Kai took his own life on his own terms in a moment of utter turmoil over peer-non acceptance which culminated with his major anxieties around all that I have spoken of above. This was the catalyst for his feelings of hopelessness and lack of will to live in a realm that offered so much pain, delusion and lacked heart. At the time he was fragile, strung out and hurting deeply. We listened, we counselled, we loved him and did not judge him for his fragility.

His memorial service was overflowing with traumatised youth who also loved him and gave testimony to his loving nature. Many spoke to us about how Kai was the go-to-guy whenever they were in crisis. He picked up those 3AM calls when his friends were feeling suicidal. All spoke of his openness and sheer ability to love with no boundries.

We have lost our beloved son. This is an immeasurable wound that we now traverse. But he has also left us, and all who knew him, with the gift of love.

Go well my love.

Camagu.

If you suspect that your child is depressed, anxious or suicidal please see the contacts below.

The South African Depression and Anxiety Group (SADAG)

Tel: +27 11 234 4837 | Fax: +27 11 234 8182 | E-mail: media@anxiety.org.za | Web: www.sadag.org

Photo Credits.

Kai Meme: Savanna Duarte.

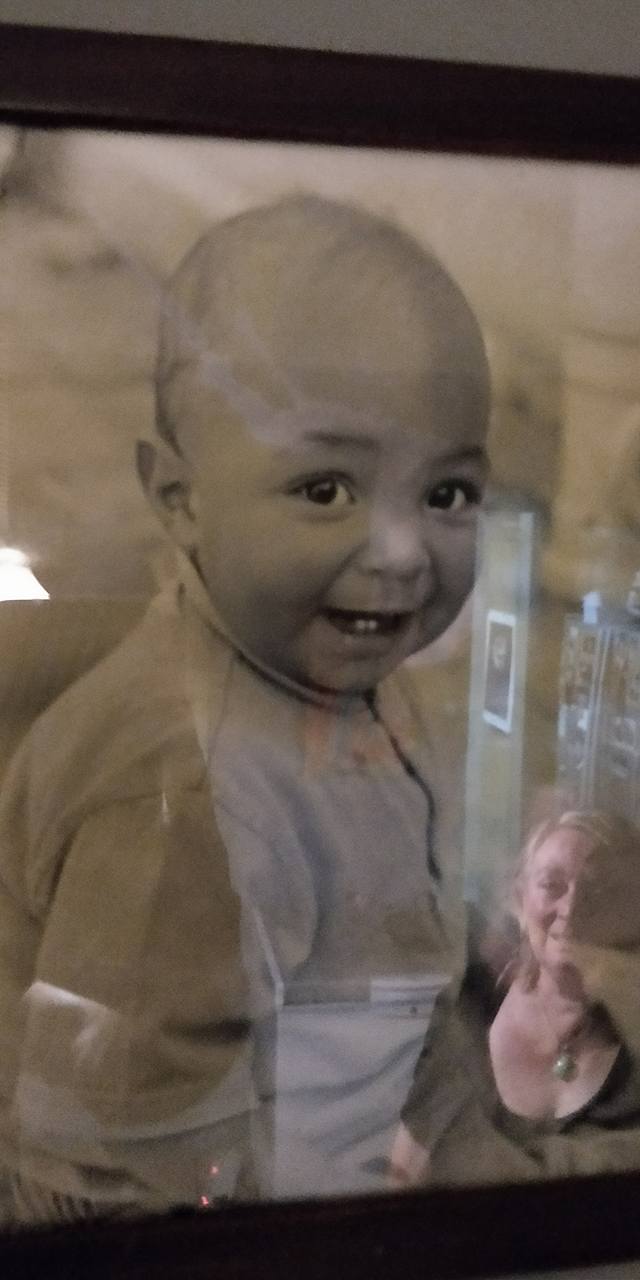

Baby Kai: Sean Flynn

Copyright: Media for Justice on all content.