By Staffwriter

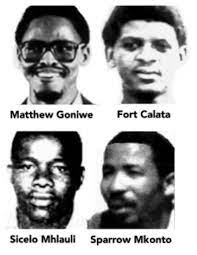

Sicelo Mhlauli—later remembered as one of the Cradock Four alongside Matthew Goniwe, Sparrow Mkhonto and Fort Calata—was born on 25 May 1949 in Cradock, Eastern Cape, the third of five children. From his earliest days, the rhythms of church hymns and freedom songs wove themselves into the fabric of his upbringing. His paternal grandmother, Makhulu, presided over a household grounded in Christian principles of love, respect and care, teaching him that family obligations extended beyond the nuclear unit. Under her watchful eye, Sicelo learned that compassion was a duty as well as a blessing.

His father, Qokosi “Tatiwe” Mhlauli, carried the weight of political conviction into every conversation, quietly hosting outlawed African National Congress meetings in the back room of their modest home. Sicelo’s aunt Ntobi lent her voice to the Congress choir, lifting freedom songs high after Sunday services at St James Anglican Church. Weekends found him lingering at clandestine ANC gatherings, absorbing debates about justice and dignity as eagerly as he savoured his grandmother’s sweet mealies. At St James Primary School he served under Canon James Calata, absorbing lessons of faith and activism in equal measure, before continuing his schooling at Cradock Bantu Secondary, where history and language first ignited his twin passions for teaching and resistance.

In 1968, Sicelo journeyed to Lovedale College near Alice to train as a teacher, determined to challenge the Bantu Education system from within. His appetite for knowledge led him to register for a Bachelor of Arts through the University of South Africa, a qualification he pursued by correspondence whenever he found a spare half‑hour between lessons and community meetings. Even then, he reached into his own meagre salary to ensure that children from families unable to pay boarding fees or afford textbooks could stay in class. To him, solidarity was both a pedagogy and a moral imperative.

Returning to the Eastern Cape in the early 1970s, he took up his first post at Masingatha High School, where he specialised in History and Afrikaans. As both sports master and boarding master, he oversaw the welfare of dozens of pupils, coaching rugby matches one afternoon and patrolling dormitories the next. When he learned of a child sent home for unpaid fees or another borrowing bread from classmates, he quietly organised staff collections to fill the gap. Discipline, he believed, was inseparable from care.

His commitment to his pupils deepened during the 1975 food strike at Thembalabantu High School. When students protested the meagre portions served at lunch, Sicelo stood beside them, negotiating with Ciskei Education Department officials until they agreed to review the menu. The Ciskei Intelligence Services took an unsettling interest in him, subjecting him to repeated interrogations and threats. He never named the instigators of the protest, honouring the trust his students placed in him, even when the price of that silence weighed heavily.

A transfer in 1977 brought Sicelo to Archie Velile Secondary School in Dimbaza, where township youths demanded democratic Student Representative Councils and equal resources. When security police descended with batons and tear gas, injuring scores of children, he loaded the bloodied and broken into his small escort car and drove them to the nearest clinic, ignoring orders to stand down. That act of defiance reverberated through the Ciskei administration, marking him as a thorn in the side of an already unstable regime.

At home, his wife Nombuyiselo—known to friends as Mbuyi—stood steadfast by his side. Their small house in Dimbaza became a sanctuary for parents fearful of police raids, a safe house for activists planning rent boycotts and a meeting place where children whispered questions about the future amid the muffled hum of clandestine gatherings. Mbuyi managed the household’s comings and goings, ensuring that guests left before dawn, while Sicelo mapped out strategies for community organising.

Beyond the township, Sicelo deepened his ties with former Robben Island prisoners who had been dumped in Dimbaza—figures such as Matthew Goniwe, his boyhood friend, and Mzwandile Gxuluwe. Under their guidance, he helped establish secret cells and taught aspiring activists to document human rights abuses. In hushed tones and shadow‑lit rooms, they laid the groundwork for the Congress of South African Students (COSAS) in local schools, believing that the struggle would be won one classroom at a time.

Fearing ever‑closer surveillance, Sicelo and Mbuyi moved to the Southern Cape, first to Colesberg and then to Oudtshoorn, where he served as principal of Fezekile High School. Within months he transferred to Colesberg Primary, only to feel the tug of destiny call him back to Oudtshoorn. There, he and Mbuyi re‑established their home as a hub of resistance. Alongside local leaders such as Reggie Oliphant, Sicelo founded the Oudtshoorn Civic Organisation and the Bhongolethu Youth Organisation, mobilising workers’ strikes, rent boycotts and learner protests. When the United Democratic Front (UDF) launched in Cape Town on 20 August 1983, he stood among the delegates carrying the Southern Cape’s banner, signing onto a united call for non‑racial democracy.

That same year saw the birth of Saamstaan, a grassroots newsletter modelled on the Eastern Cape’s Grassroots paper. Sicelo joined its editorial board, overseeing dispatches on forced removals, police atrocities and denied services, while shadowy presses churned out copies that activists carried into churches and taxi ranks. His home echoed with the hum of mimeograph machines and the whispered flourishes of reporters eager to expose the regime’s brutalities. In every leaflet they printed, Sicelo heard the rising chorus of a nation refusing to be silenced.

In June 1985, Sicelo returned to Cradock for the annual celebration of the Freedom Charter. Alongside Matthew Goniwe, Sparrow Mkhonto and Fort Calata—four voices of defiance destined for infamy—he joined the Cradock Residents Association delegation heading to a UDF meeting in Port Elizabeth. They spoke of rent boycotts and stay‑aways, of the power of collective action. But on the night of 27 June, security forces abducted them. When dawn came with no word of their whereabouts, a panic spread through the activist network. The next day, their bodies were discovered near Bluewater Bay, their mutilations a grotesque testament to state terror. Sicelo’s corpse bore twenty‑five stab wounds and a severed hand; what remained of his humanity lay scorched by the same fire that consumed his hope of release.

Grief rippled through the country, and his widow Mbuyi emerged as the family’s fiercest advocate. She pursued successive inquests, interrogating former intelligence officers and demanding accountability. Even after the first democratic elections in 1994, she refused to rest, her quest for truth emblematic of a nation still wrestling with the legacy of apartheid’s violence. Though some perpetrators faced trial, the full truth of that night in June has never been declared, leaving Sicelo’s memory suspended between martyrdom and mystery.

Yet his legacy endures in the many lives he touched. Former pupils recall how he transformed dusty archives into vivid tales, how he animated the past to instil courage in their present. They speak of his booming laughter echoing through school halls, his dramatic reenactments of nineteenth‑century battles that left them breathless and thoughtful. They remember the afternoons he helped them navigate the complexities of Afrikaans grammar and the evenings he coaxed them to sing freedom songs while returning home from sports fixtures.

At home, Sicelo was a devoted father to Babalwa and Ntsika, guiding their curiosity with gentle humour. Weekends found them exploring the rugged beauty of the Cango Caves or winding along Meiringspoort, the car’s upholstery a makeshift stage for his favourite radio broadcasts. He would lie flat on the floor, eyes closed, absorbing every note of Radio Freedom—speeches by Dr OR Tambo interlaced with the voices of exiled leaders and the rhythm of struggle songs. Before long, the children joined in, their laughter mingling with the music as the small car became a vessel of hope.

His sister‑in‑law recalled that whenever a neighbour faced eviction or a family was too frightened to petition for services, Sicelo took them under his wing. He opened his home to strangers, fed them, clothed them and, most importantly, convinced them that resistance was not merely possible but indispensable. He believed that every act of kindness was an act of rebellion, that the true measure of freedom lay in our willingness to risk comfort for the sake of another’s dignity.

Nearly forty years after his murder, Sicelo’s name graces school halls and lecture theatres, his story taught as both history and inspiration. Annual memorial services recall his death alongside Matthew, Sparrow and Fort, underscoring how four lives cut short galvanised a nation towards its democratic destiny. The newsletters he helped publish have evolved into legitimate local media, and the civic organisations he seeded continue to champion community rights.

His life reminds us that freedom is seldom won by grand gestures alone. More often it is forged in classrooms where teachers refuse to lie, in homes where families open their doors against terror, and in car rides where the song of liberation drowns out fear. Sicelo Mhlauli’s sacrifice calls on each generation to carry forward the unfinished work of justice, to speak truth to power and to believe that even the smallest voice—raised in song or spoken in defiance—can change the course of history.