By Gillian Schutte

Cancel Culture proliferated on campuses across South Africa around 2016 – when the Fees Must Fall campaign was in its second year. It developed out of intersectional feminism premised on Kimberlé Crenshaw’s salient work in the late 1980’s. Hers was a call for an intersectional legal approach, that “recognised multiple and overlapping points of oppression.” In a nutshell a google search describes intersectionality as the study of overlapping or intersecting social identities and related systems of oppression, domination, or discrimination. Crenshaw’s work offered the space for “radical and complex analysis of power and limitations.”

However, in the 21st Century neoliberal terrain of hyper-capitalisation and competitiveness, what we are seeing instead, is that intersectionality has been reduced to a type of moral fundamentalism that diminishes levels of analysis to an individual rather than collective level. Crenshaw’s perfectly sound and necessary theory has been distorted, repackaged and weaponised in the hands of many youth who now have the opportunity to deform its tenets to take out individuals rather than fight the systemic injustices that are presented by neoliberal hegemony. I have coined this contamination of pure intersectional theory by neoliberal ideology ‘neo-intersectionality’.

As a filmmaker and journalist who covered Fees Must Fall for two years, I witnessed the gradual implosion of Fees Must Fall beginning at the moment intersectional politics was introduced onto campuses – significantly at a time when the movement had shown no signs of defeat and was gathering national momentum. While at first the interest in intersectionality appeared to be a positive move to address questions of power and identity, it was quickly hijacked and weaponised by neoliberal ideology and subsequently morphed into neo-intersectionality. This was seen in a notable shifting of the student focus away from intersectionality in its pure form towards rampant individualism in which charismatic characters performed for careerism and social currency – behaviours that are encouraged and heightened within a neoliberal context. In this way the revolutionary focus of Fees Must Fall to attain a free and fair education for all as well as radical socioeconomic justice for the oppressed African majority, was soon shifted from matters of challenging and dismantling neoliberal hegemony and instead became largely focused on the Black Male leaders of Fees Must Fall as the oppressors.

On the surface the wokeism that grew out of intersectional discourse seemingly framed Black women as only victims to Black men and Black men as only perpetrators. It was this wokeism that gave rise to subcultures such as the #menaretrash movement in which mostly Black men, with a particular focus on the leaders of Fees Must Fall, were being called out/cancelled for patriarchal behaviours and sexual assault. In this way the #menaretrash meme contained an obvious racial and gender bias that apparently overlooked the problematising of white masculinities. Corporate media showed a marked interest in this aspect of Fees Must Fall and soon News headlines were focused on gender disparities and Black male violence within the movement, giving social platforms to those who became intersectional spokespeople.

On the one hand this went some way to focus the often overlooked social historical victimisation of Black women through systemic marginalisation and highlighted gender based violence as the scourge that it is. This created valuable space for these conversations and debates that were sorely lacking in South Africa. On the other hand, these spaces were also intercepted by the will of individuals to take out those men who were seen to be usurping the leadership roles in Fees Must Fall. At this point an unprecedented number of male FMF leaders were accused of either sexual assault or rape and it was hard to fathom these unusually high stats without suspecting that social engineering and paid infiltrators were behind this statistical nightmare. This onslaught seemed to follow the ‘Monsterisation of Black Men’ logic of Judge Mabel Jansen when she declared on a public platform that: “rape is part of black culture” and that she is “yet to meet a black woman who was not raped by the age of twelve.” She went on to add (in my inbox) that “a women is there to pleasure” men, that women tell their children it is their father’s birth right to be the first, and that gang rapes of baby, mother and daughter were a “pleasurable pass time of Black men.”

At this juncture a number of radical feminists had moved into leadership positions on the picket lines and elsewhere and it must be noted that their struggle to be taken seriously as leaders was a battle worth fighting and one that yielded positive results. Around the same time we saw individuals from marginalised and often stigmatised identity groups begin to challenge the movements structures for the recognition of their role in the struggle. What was a valid challenge soon fell victim to neoliberal meddling and became another thread in the infighting. Here trans-identified persons proclaimed their added subjugation from other groups within the queer collective while the queer collective referred to radical feminists as patriarchal princesses who were using their feminine wiles in heteronormative structures for power. This discourse went on to challenge the validity of anything that was considered heteronormative with an insistence that all heterosexual leaders were the primary oppressors of all other identity groups and thus had to be removed from the leadership structures. Leadership structures were deemed only valid if the hierarchy of ‘who was most oppressed’ was adhered to. In addition, the intersection between radical feminists and queer groups gave rise to their collective disavowing of the vast canon of radical Black Consciousness work such as that of Steve Biko, Frans Fanon and Robert Sobukwe; declaring these texts non-worthy as they are steeped in patriarchy.

While the gender wars raged on it became evident that the mandate for a socially engineered identity ‘conflict situation’ was mostly an attempt to eradicate the influence of Black Consciousness (BC) and to break the power base of the mostly Black male leaders; notably those with BC ideology. This largely happened via personal attack on individual leaders, along with reputational damage that easily found its way into the corporate press. The threat of having your name associated with rape was a weapon in itself and this is the fate that befell many of the leaders. It was largely these men who alone ended up being incarcerated for long stretches when the state turned its full arsenal on the movement.

In my view this is indicative of an obvious drive to dismantle these leader’s successful radical mobilisation of the majority of students against the hegemony. The utter annihilation of student unity was the main target of this systemic interception of the movement by anti-revolutionary forces taking advantage of what could have been an important theoretical moment. This they did through liberal academics who wilfully diminish the true tenets of intersectional theory by stripping it of the historical colonial context as well as eradicating its critical race theory tenets – thereby reducing it to gender identity alone. It is a well-known method utilised by embedded liberal White academics, many of them women, who feel that by virtue of being women their experience of oppression is on a par with Black women’s lived experience. In this way Black men are then able to be treated as being on a par with White men and thus framed as equally oppressive, both individually and systemically. While all men have the choice to be individually oppressive the problem lies in the equating of Black men’s lack of systemic power with that of the historically entrenched systemic power accrued to White men – and it was this problematic pedagogy that gave rise to many of the confrontations and breakages in the student movement.

This diminished ahistorical form of intersectionality, with its individualistic, fundamentalist and moralistic usage of wokeism and cancel culture, quickly engulfed the very real fact that White economic and cultural hegemony, sustained by the ANC, is where patriarchy and hierarchical placement of identities is systematically entrenched. Instead, a myopic analysis of power turned inwards and as a result the movement was systematically fractured from within. Some argue that this was a strategically devised interception that followed the blueprint of the apartheid special ops/stratcom programme to create a form of black-on-black violence.

And this is not to say that all the proponents of intersectional theory were engaged in this weaponised form of intersectional politics because there were also necessary and fruitful engagements around power and its limits within the movement that worked for gender justice and justice for victims of abuse. But what seemed to supersede this was a disregarding of the necessary unity required to dismantle the monster metanarrative of neoliberal hegemony along with the problem of White hegemony. As a result, the Fees Must Fall movement quickly disintegrated into in-fighting between different identity groups in what appeared to be a bunfight for power, and notably power for individuals within these groups – a phenomenon that smacked of social engineering from neoliberal think-tanks with US intelligence links that are adept at intercepting and weaponising identity politics at critical moments in successful peoples’ movements in a clear attempt to smash potential revolutions.

Funzani Ne-Tshivhazwaulu, a former Fees Must Fall leader, says that: “the systemic weaponisation of what were meant to be useful and necessary tools for justice, such as ethical cancel culture and wokeness, has worked to trivialise the real experiences of Black women and made people more distrusting and questioning of victimhood, even when victimhood is justified.”

Beyond Fees Must Fall

It would seem then that even rightful victims have been further victimised by this phenomenon and the use of weaponised wokeism and cancel-culture has left many innocent victims in its wake. Unfortunately, this diminished form of intersectional ideology has remained on campuses across South Africa and saturated the sociocultural thinking of the 21st Century youth – where it continues to flourish in a manner so divisive that it underscores my hypothesis that the neoliberal system has encouraged this discourse though liberal press, liberal academics and an NGO funding drive with a corporatised mandate to eradicate the possibility of collective youth power taking down the system. This has become a phenomenon that calculatedly accrues a lot of power to selected youths in terms of their chosen identity in a jostle for personal authority rather than collective justice.

But more specifically it has accrued power to individuals, mostly those who have currency, whether through economic privilege or social media influence. The majority of youth it seems, become the vassals of those youth who are handed the opportunity to climb the social ladder as influencers and become mini-me CEO’s that dispense and enact their power on their subjects. In this way the advent of neo-intersectional ideology reflects the corporate culture more closely than the drive for egalitarianism inherent in pure intersectionality. Neo-intersectional theory and its enfant terrible, cancel culture, is now a weapon that the youth easily wield to take each other out in a fight for personal power, to settle petty arguments or simply because they can.

The problem is that when it comes to 19-year-old (and younger) individuals accumulating this power, especially at a time when their maturity is not completed and their inner world is often a tumultuous hybrid of hormones, emotions, seeking of peer approval and desiring social status, things can, and have, gone horribly wrong. This is most obviously seen in the rise of mental breakdown and suicide statistics among the youth who have found themselves on the receiving end of a cancel campaign.

What could have been a reasonable and positive discourse has been weaponised by the individualistic predatory values of neoliberalism. And while there is value in calling out the system for protecting those with power from their horrific abuses of power, the wider socially engineered and calculated dissemination of cancel culture, I argue, has never really been about the constructive calling-out of friends to account for unacceptable behaviours. Rather it has been an engineered move to turn the call for accountability away from those in power onto the ordinary person with no power, as a way to further shatter and disempower the collective.

That some of our children have either seized or been given the ‘artillery’ to dispense this power over others ought to be as horrifying to us as war is. They are the new child soldier mercenaries – albeit discourse mercenaries – and they are merciless in their quest for personal power and status. They receive accolades for their felling of their adversaries through clicks, likes, mass adulation and social media popularity in the same way that mercenaries are rewarded for taking out the perceived enemies of imperialism. As a result our social landscape continues to be littered with the injured and dead bodies of the youths who become victim to this heartless phenomenon. My own son Kai Singiswa, is one of them. Read his story here. (KOP, Cancel Culture and the suicide of Kai Singiswa)

Given this alarming rise in youth suicide statistics surely the time is now for the legal system to hold these cancel culture perpetrators legally accountable for the consequences of their merciless power-based behaviours that result in the death of their peers. This virtual killing spree must end and we must insist on justice for victims of cancel-culture because any of our children could find themselves on the receiving end of this and choose suicide as as a way out of the untenable distress this creates for them.

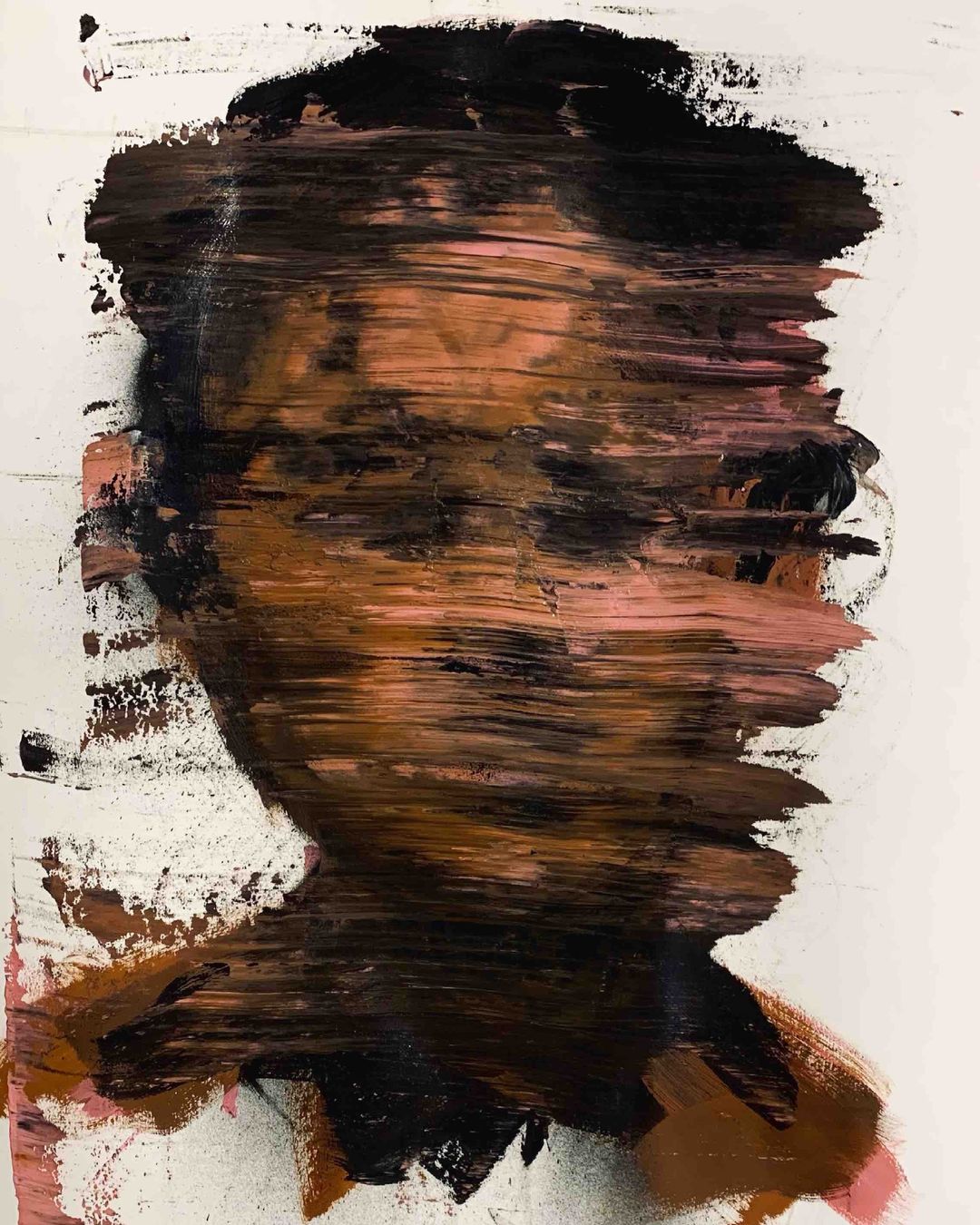

Image: Courtesy of Seth Pimentel (b. 1995 – Johannesburg, RSA)Seth is an illustrator, painter and experimental visual artist who is currently living and working in Johannesburg.

Instagram- african_ginger

NOTICE

If you are feeling suicidal, depressed or anxious please contact SADAG

To Contact A Counsellor Between 8am-8pm Monday To Sunday,

Call: 011 234 4837 / Fax Number: 011 234 8182

For A Suicidal Emergency Contact Us On 0800 567 567

24hr Helpline 0800 456 789