The politics of language in post-apartheid South Africa

By: Bhekumuzi Abdul Shabalala

In his seminal non-fiction work Decolonising the Mind: the Politics of Language in African Literature, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o evaluates the complicit role of language in literature and elsewhere in consolidating some of the ongoing contradictions in post-colonial Africa. Likewise, the present essay, although brief, follows in that tradition – with the hope to recast language dynamics as an equally relevant site of analysis in the dialogue around the idea of a ‘post’-apartheid South Africa.

There is no universally accepted definition of ‘imperialism’ in political science. But there is a general consensus among academics that stresses its multidimensional nature – it is not only political and economic but cultural and, more importantly for present purposes, linguistic as well. The imperialist advances into South Africa from the second half of the 17th century diminished the use and status of African indigenous languages and this persisted right up to the mid-1990s, at least formally.

Against the backdrop of the historical marginalisation of indigenous languages and the cultural subordination attendant to it, the new Constitution has provisions that seek to correct this. Section 6 provides for the equal status and use of all the official languages in South Africa, the majority of which are indigenous. Over two decades into the new dispensation, however, it is interesting to note that little has changed with regard to language dynamics in South Africa – not only as they relate to official and administrative functions but even in personal spaces that may not be regulated through the agency of the law.

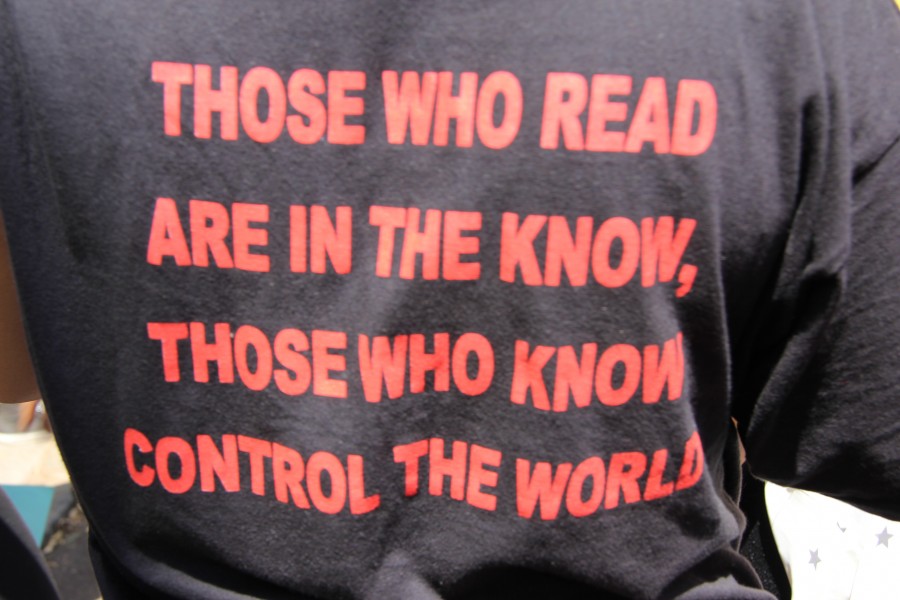

South Africa is multilingual and although the different languages in principle have equal status, an adequate command of the English language is largely an important prerequisite for success in one’s academic and professional endeavours. Moreover, it enables one to be accepted into exclusive social circles and participate in activities that one would otherwise not have access to. For these and other benefits that attach to having a facility of expression in English, it is the only language that is offered as a compulsory learning area at the pre-tertiary schooling level in South Africa.

By contrast, African indigenous languages occupy a relatively subordinate position to English. They are optional in the pre-tertiary curricula and in schools where they are offered, it is predominantly black students that are enrolled. The effect this has is that although the majority of black people can speak in and understand at least some basic English, their white counterparts are largely unable to express themselves in any of the indigenous languages. This does not only reflect indifference on the part of most white people to integrate into the indigenous cultures but it is an index of socio-economic polarisation in ‘post’-apartheid South Africa.

The black majority, as a result of the political compromises made at the negotiating tables, bears the brunt of structural inequality, dispossession, unemployment, skewed spatial arrangements as well as the other material contradictions in ‘post’-apartheid South Africa. White people, however, generally have access to, and control over, the economy and other important institutions in society, such as universities, which in their totality enables them to wield their dominance with a sledgehammer. Because of these asymmetries, black people generally have to be able to express themselves in English so that they could be accepted into white spaces and advance financially and otherwise. However, white people have no incentive to learn indigenous languages because they often never have to appeal to black establishments for employment, education and any other benefit that is bound up with social mobility.

A possible counterargument that I anticipate is one that suggests that the pervasive use of English is alright to the extent that it acts as a lingua franca – facilitating communication among people from diverse cultural, geographic and linguistic backgrounds. From an entirely functionalist perspective, this argument is sound. However, the assumption it is built on is problematic. The choice of a common language is not random nor based within the moral framework of common consent, but instead ought to be understood as a deliberate outcome of historical processes, in our case colonialism. Therefore, any argument that assumes that the status quo is unchangeable is not only misplaced but even takes away from our efforts as black people to self-organise and assert ourselves in a world that is least favourable to us.

It is therefore obvious from the above discussion that language dynamics – in addition to other sites of analysis – undermine the idea of a ‘post’-apartheid South Africa to the extent that unequal power relations between the different racial groups persist.

Bhekumuzi Abdul Shabalala is a second-year Law student at the University of the Witwatersrand whose intellectual interests span philosophical pessimism, the antinatalist movement, Christian iconography, pulp fiction and intersectional politics.

Twitter: @AbdulShabalala

Facebook: Bhekumuzi Abdul Shabalala