By: Brenden Gray

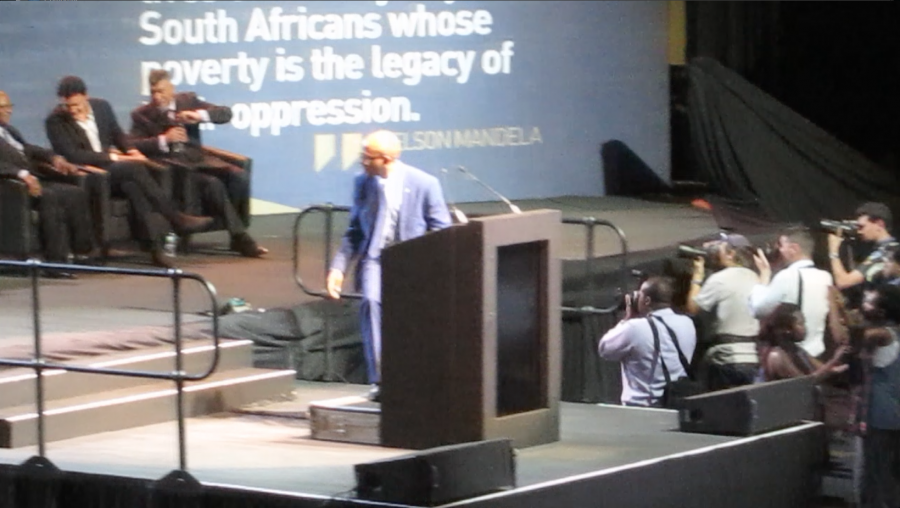

On Saturday afternoon I attended the 2015 Annual Nelson Mandela lecture at the UJ Soweto campus, which was delivered by Thomas Piketty, the French economist and author of Capital in the 21st Century. Here is a loose summary, and few off-the-cuff observations and impressions (developing into a more substantial piece).

It was a completely red carpet, elite affair comprised of academic, business and political elite who seemed to be at the Imbizo Hall to do what elites do best: network. It struck me as more than ironic to see what are poorly paid and exploited outsourced workers everywhere servicing the needs of this elite – collecting their rubbish, mopping up their mess, guiding them to their seats, cleaning toilets, guarding their vehicles and personal possessions. The venue divided the audience into the VIP’s who sat on comfortable seats below and the others who sat on plastic stadium seats in the flanking galleries above. The VIP section at the very front was reserved for stalwarts, business leaders, functionaries, policy-makers, high-ranking government officials, university management. The event was hosted by UJ and lavishly sponsored by various prominent corporates, among them, Vodocom, AngloGold Ashanti, Coca Cola, Audi, Rupert and Rothschild, Nashua, Douw & Carolyn Steyn, SABC. Amongst them, oddly, was the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation. Large blue and gold coloured banners hung from the walls depicting Thomas Piketty and Nelson Mandela as icons rendering their faces in the intaglio style of the bank note. The audience was asked to stand and sing the national anthem before the proceedings began. The entire ensemble was, in the words of SABC anchor Francis Herd, “elegant indeed”, a somewhat weird and incongruous observation given that the lecture was about inequality.

There seemed an obvious attempt on the part of all of the introductory speakers to suppress Karl Marx and Marxist discourses on capital despite the obvious relevance of these ideas to Piketty’s research and to play up discourses of liberalism. Piketty’s book was compared by the MC in terms of its length to Tolstoy’s War and Peace, the Bible and so on but not to Das Kapital; a glaring omission that was observed throughout the proceedings. I got the sense that the event may have in fact been designed to displace Marxism as irrelevant and anachronistic. I also got the sense that the invocation of the legacy of the late Nelson Mandela was used to endorse this displacement and (as it so often is), to neutralise revolutionary ideas around capital and to nullify discourses of economic injustice in favour of more liberal ones of racial reconciliation in South Africa.

My first thought was that the event may have been designed not only to displace the dominance of Marxism in scholarly discourses on capitalism but also to to co-opt Thomas Piketty into a liberal and neoliberal agenda. I got the sense that this strategy went horribly wrong because the organisers of the event and their associates failed to see (either because few read his book ‘Capital in the 21st Century’ or read it but with little or no understanding) that, relative to their own neoliberal conservativism, Piketty is actually quite radical. Unexpectedly, Piketty not only delivered a socialist message (albeit socialist-lite), but gave a coherent, social democratic critique of South African neoliberal policy. It seemed clear from their brief statements that neither Njubulo Ndebele (Chancellor University of Johannesburg), Ihron Rensburg (Vice Chancellor University of Johannesburg) nor Sello Hatang (CEO Nelson Mandela Foundation) were prepared for this. It seemed to me that none had engaged substantively nor directly with the ideas in his book nor Piketty’s views on democracy and neoliberalism. All offered the usual boring, normative cliches to characterise poverty and inequality using extremely general terms that almost bordered on the absurd. “Poverty and inequality threaten to unravel [the dream]” (Ndebele). What dream is that? Whose dream is that? Why is it still a dream and not a reality? “Failure to succeed may […] under our watch mean the end of nation states and human society as we know it” (Rensburg). Under whose watch is that? Who is ‘our’? “How do we overcome oppressive patterns of inequality?” (Hatang). Surely it is oppression that creates patterns inequality and not vice versa?

Each in his own way thought of inequality as the underlying problem (the enemy of the dream, the opponent of democracy, a demon to be overcome) and not a symptom of a deeper structural problem. I think it came as a surprise to them all and many in the audience that Piketty, rather than continue the line of vague, platitudinous rhetoric, actually presented a critique and a provocation.

Piketty was not at all vague about inequality in his lecture. For him, South African inequality is extreme, untenable and entirely unacceptable. The root cause is continuing and entrenched white privilege, the ascendance of global corporate power, policy and political failure and continued colonial relations. He emphasised that policy informed by the blind neoliberal valorisation of growth, market- oriented, trickle-down solutions to social problems (of which I count GEAR and the NDP) are not only false, but in fact make a major contribution to creating inequality and poverty. Neoliberal policies actively serve elite interests, undermine the state and fail the poor. There is much evidence to this effect (see Patrick Bond: ‘Why inequality will not be fixed with Pikettian posturing and distorted data’). Market values and commodification ultimately exacerbate social tension, provokes conflict and ultimately results in the kind of repression and violence as was seen at Marikana in 2012.

Piketty’s main point was that, under the present conditions of radical, structural inequality in South Africa, the provision of ‘equal rights’ are not enough. Alone they cannot ensure that everyone receives their fair share in the national product. The economic mechanisms and circumstances underwriting the inequality, as they exist in South Africa in the present – historical concentrations of wealth derived from colonialism and apartheid, wealth reproduced through inheritance, large returns on capital, legal protection of private property rights, unfair advantages in what is a largely unregulated market, the influence of money over political processes, financialisation, offshoring profits, globalisation and so on – are simply too powerful to be resolved by giving citizens equal chances to compete for their share of the national product on an open market. In order to achieve greater levels of equality, substantive, redistributive rights are not a nice to have. They are essential. These rights must be enforced by the state. For Piketty, only such an approach can counterbalance the economic mechanisms that are the source of inequality and injustice, especially in a country like South Africa.

He suggests the following four sets of rights are put in place to address the situation:

1.The right to access a decent wage and work without exploitation.

2. Universal access to high functioning, free, public education.

3. Access to property rights and especially land.

4. Democratic worker participation in the workplace.

He added to this list, access to information (such as that related to wealth and ownership patterns). Without it the democratic and redistributive capacity of the state would be seriously undermined. This kind information crucial to its functioning (wealth data useful to develop innovative capital tax) is increasingly controlled and owned by private concerns rather than publicly owned and accessible.

These are laudable proposals if you are a social democrat and a European one at that. But there are problems with such an approach both conceptually and politically. In his lecture, Piketty relies heavily on the notion that there are peaceful (ie. non-revolutionary) solutions to class conflict and supposes that governments can, in reality, function on an egalitarian basis. In his mind, the redistributive functions of government would be supported by effective taxation strategies and deeper democratic practice. Here, the state is largely characterised as benevolent entity, heavily invested in the ethics of sharing. He constantly refers to the ideal of egalitarianism in Capital in the 21st Century. “Sharing the national income”, “labour’s share in national wealth”, “the share of the top decile”, “capital’s share”, “share of income”, “share of wealth”. How is this egalitarianism framed? Interestingly, Piketty asks “in an ideal society, how would one arrange the division between labour and capital”?

Posing the question thus suggest that in the author’s mind, the division between labour and capital is inevitable and natural. That would mean that there will always be capitalists and there will always be labourers and given this, a state must be formed to adjudicate and modernised to stabilise society. We must accept these arrangements as given. But more to the point, for Piketty, an ideal society still remains a capitalist society. Capitalism is ideal so long as the social costs of capitalism (of which inequality is one and conflict is another) is properly managed by responsible governments and properly regulated by democratic practices. Piketty never suggests that an ideal society may be a classless one, or a post-capitalist society. At no point in his lecture did he critique capitalist relations. It seems that for Piketty, the ideal society is one where class conflict has been ironed out by a benevolent and well-designed state apparatus that ironically, enforces, through its legitimate monopoly on violence, universal fairness and sharing.

Piketty compared South Africa to France in terms of the failures of the revolution to bring about enduring and meaningful social change suggesting that South Africa’s was a bourgeois revolution failing to reach its own goals. Rather than proposing a further revolution his lecture calls for a social reorganisation but firmly within capitalist relations. As such, his ideological message aligns nicely with the power sharing discourses of national reconciliation and the Rainbow Nation of which Nelson Mandela was so fond whilst at the same time supporting a big, welfarist government and through it a bureaucratic, elite managerial class. If his work presents a problem for neoliberalism it does not present a real challenge because it never really gets to the heart of what causes inequality and class conflict in society in the first place: capitalist relations.

Ultimately without thinking through what Erik Olin-Wright might call the “causative mechanisms” behind class inequality, Piketty operates within the conservative framework of a ‘just capitalism’ or ‘stakeholder capitalism’ taking exploitative social arrangements as given rather than making them subject to radical change. His book largely takes the tensions between labour and capital as given. The state mediating this tension in perpetuum meaning that changing the actual relations that create the tensions in the first place can be changed.

Piketty fails to give an account of why, historically, the relationship between labour, state and capital is antagonistic. Marx suggests that at the root of this antagonism lies the inordinate ability of the capitalist class (usually also the ruling class) to exploit other groups. So long as individual private property rights remain sovereign, ownership of the means of production is concentrated in the hands of the few and the state functions to guarantee this, there will always be poverty, inequality and with it social suffering, crime, conflict, violence. Inequality arises not from the technical and moral failure of society to share as it were – as Piketty would suggest – but rather arises directly from exploitative practices of owners which is, as history tells us, in fact often enforced aggressively by the state. It is the actively exploitative practices of capital, encouraged by the neoliberal state, that accounts for capital’s rising share of the national income and the massive disparities in wealth that occur in societies everywhere. Only a Marxist approach address these issues and yet Piketty was silent on this in his lecture, probably for political reasons. Given this, should we look to Piketty to explain inequality or even look to him for arguments as to how and why it should be eliminated and for what reason? Perhaps what he offers is modest: a clear picture of inequality under capitalism.

Njabulo Ndebele, in his introductory address, might have reminded the audience when he discussed the Freedom Charter (before he quickly jumped to praising our liberal Constitution) that fully realising the “dream of all who live in South Africa” must become a reality through restorative justice. To quote the Freedom Charter:

“The national wealth of our country, the heritage of South Africans, shall be restored to the people; the mineral wealth beneath the soil, the Banks and monopoly industry shall be transferred to the ownership of the people as a whole; all other industry and trade shall be controlled to assist the wellbeing of the people”.

How can inequality be eradicated if doing so requires that the “people are not fighting for ideas, for the things in anyone’s heads” but “fighting to win material benefits” (Cabral). Dealing with the material basis of inequality is becoming more and more urgent. Pedalling “hope” that we can be “doing things differently” (as Hatang put it in closing the proceedings) may simply be deliberate strategy by the elite to indefinitely defer the coming of the people. Some in the audience cheered at the moments when Piketty touched on the raw nerve of ownership. The front row was chillingly quite when they did. I could imagine Trevor Manuel tensing at every cheer.

Brenden Gray is a Johannesburg-based social theorist.

brendenyeo@gmail.com

Hey! I just wish to give an enormous thumbs up for the good information you have got right here on this post. I will be coming again to your weblog for extra soon.

you’re in reality a good webmaster. The web site loading velocity is incredible. It sort of feels that you’re doing any unique trick. Furthermore, The contents are masterwork. you’ve performed a excellent process on this subject!

Propecia Verschreiben Lassen [url=http://prozac.ccrpdc.com/prozac-definition.php]Prozac Definition[/url] Comprar Viagra India Viagra Y Prostatitis [url=http://cial1.xyz/shop-cialis-online.php]Shop Cialis Online[/url] Prescription Drugs From Canada Online Buy Viagra Without A Prescription [url=http://zol1.xyz/zoloft-50mg.php]Zoloft 50mg[/url] Cialis 10mg Reviews Celexa Online No Prescription [url=http://cial5mg.xyz/fast-delivery-cialis.php]Fast Delivery Cialis[/url] Prix Du Cialis 10mg En Pharmacie Impotencia Propecia [url=http://viag1.xyz/order-viagra-pills.php]Order Viagra Pills[/url] Zithromax Otitis Media Where Can I Buy Tretinoin Online Uk [url=http://viag1.xyz/low-price-viagra.php]Low Price Viagra[/url] Trimohills Canine Cephalexin Dosage [url=http://viag1.xyz/viagra-online-prices.php]Viagra Online Prices[/url] Zithromax Injection Progesterone 300mg Without Rx [url=http://cial5mg.xyz/cheap-cialis-20mg.php]Cheap Cialis 20mg[/url] Order Amoxicillin Overnight Shipping Finasteride Tablets For Sale [url=http://viag1.xyz/best-viagra-online.php]Best Viagra Online[/url] Efectos Secundarios Cialis 20 Mg Buy Viagra Blue Pill [url=http://zol1.xyz/cost-of-zoloft.php]Cost Of Zoloft[/url] Propecia Usa No Prescription Is Cephalexin Good For Vaginal Infections [url=http://cial5mg.xyz/how-to-buy-cialis.php]How To Buy Cialis[/url] Buy Ampicillin 500mg No Prescription F [url=http://zol1.xyz/zoloft-50mg.php]Zoloft 50mg[/url] Propecia Cutaneo Amoxicillin And Leave And Body [url=http://kama1.xyz/kamagra-jelly-usa.php]Kamagra Jelly Usa[/url] Order Alli Diet Pills To Canada Latente Propecia [url=http://cial1.xyz/cheap-cialis.php]Cheap Cialis[/url] Amoxicillin And Cipro And Drug Class Amoxicillin Drink Coffee [url=http://kama1.xyz/how-to-get-kamagra.php]How To Get Kamagra[/url] Can You Take Amoxicillin With Aspirin Acheter Propecia Finasteride [url=http://cial1.xyz/cialis-free-offer.php]Cialis Free Offer[/url] Viagra Nur Auf Rezept Kamagra Tabs [url=http://zol1.xyz/generic-zoloft-usa.php]Generic Zoloft Usa[/url] Cialis Ojos Buy Propecia For Women [url=http://zol1.xyz/ordering-zoloft-online.php]Ordering Zoloft Online[/url] Tetracycline Antibiotics For Sale Zithromax For Sale [url=http://zol1.xyz/zoloft-on-line.php]Zoloft On Line[/url] Amoxicillin Chewable Tablets Food Interactions Viagra Ou Cialis Ordonnance [url=http://kama1.xyz/kamagra-gel-online.php]Kamagra Gel Online[/url] Cialis Fertilita Zithromax And Coumadin [url=http://cial1.xyz/cialis-free-trial.php]Cialis Free Trial[/url] Cialis Viagra Levitra Differenze Generique Xenical [url=http://cial5mg.xyz/cialis-on-line.php]Cialis On Line[/url] Achat Lioresal Novartis Propecia Ejaculation Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia [url=http://cial5mg.xyz/tadalafil-online.php]Tadalafil Online[/url] Is Buying Vigira On Line Safe Kamagra Per Nachnahme [url=http://viag1.xyz/buy-cheap-viagra.php]Buy Cheap Viagra[/url] Viagra Costo In Italia Canada Pharmacy Online No Script [url=http://cial1.xyz/how-to-order-cialis.php]How To Order Cialis[/url] Finasteride Nausea Propecia Cialis Brand Name Pills To Buy [url=http://cial5mg.xyz/tadalafil.php]?Tadalafil[/url] Kamagra Sildenafil 100mg Is Reconstituted Amoxicillin Still Good [url=http://prednisone.ccrpdc.com/online-deltasone-buy.php]Online Deltasone Buy[/url] Amoxil K Clav Buy Cialis 40 Mg No Prescription [url=http://viagra.ccrpdc.com/price-generic-viagra.php]Price Generic Viagra[/url] Acheter Du Cialis En Ligne Buy Viagra Online Paypal Uk [url=http://cial5mg.xyz/purchase-cialis.php]Purchase Cialis[/url] Levitra Risposta Achat Viagra Danger [url=http://nolvadex.ccrpdc.com/nolvadex-online-for-sale.php]Nolvadex Online For Sale[/url] Buying Doxycycline Online Uk Safe Buspar Overnight Shipping [url=http://viag1.xyz/viagra-discount-sales.php]Viagra Discount Sales[/url] Clomid Et Grossesse Posologie Levitra Usa [url=http://cial5mg.xyz/generic-cialis-pricing.php]Generic Cialis Pricing[/url] Where To Purchase Progesterone 400mg Wokingham Cialis 80 Mg [url=http://zol1.xyz/buying-zoloft-online.php]Buying Zoloft Online[/url] Amoxicillin For Sore Throat discount generic accutane [url=http://kama1.xyz/kamagra-price.php]Kamagra Price[/url] Achat Baclofen En Canada Canadian Generic No Presciption [url=http://viag1.xyz/where-to-buy-viagra.php]Where To Buy Viagra[/url] Viagra E Terapia Antipertensiva Tomar Viagra [url=http://accutane.ccrpdc.com/accutane-buy-online.php]Accutane Buy Online[/url] Buy Synthroid Online Zithromax 3 Day Pack Dosage [url=http://strattera.ccrpdc.com/strattera-versus-adderall.php]Strattera Versus Adderall[/url] Cheap Levitra Online